Our First Ever People’s Inspiration Meeting

Naomi Alexander, artistic director of Brighton People’s Theatre, is feeling nervous. She’s tacked a huge sheet of bright blue nylon to a wall in Brighthelm Community Centre and invited a group of 20 or so people to cover it in orange pieces of paper, on each of which is written a question. Whose education matters? Does Brighton have an identity problem? What’s the impact of gentrification? Why are mental health services so inadequate? Should we abolish Christmas?

We’ll come back to how those questions were decided on in a moment: for now, it’s crunch time. Naomi has given everyone in the room three sticky blue dots each and, like a nicer, less smarmy version of Simon Cowell, invited them to place their votes. What question would you most be interested in seeing Brighton People’s Theatre transform into a play or performance? As dots begin to smatter the orange paper, she admits to feeling not just excited but anxious, because where they land potentially decides the course not only of BPT, but: “the next few years of my life!”

That’s the premise behind BPT’s first People’s Inspiration Meeting, a gathering to which anyone who lives in Brighton is invited, to discuss what matters to them, what kind of art they like, and what kind of work they would want BPT to create. The meeting has been scheduled after a full year of other BPT activity – including workshops in performing, writing or directing, play-reading groups, and post-show discussions – and feels like the first step towards a next stage: making an actual work together. That work could be anything, from a show for a big theatre like the Dome, to a performance that happens in Brighton’s streets. The point is for the people of Brighton to be involved at every stage, from the very first inkling of the idea to the fading light on the final performance.

That’s the premise behind BPT’s first People’s Inspiration Meeting, a gathering to which anyone who lives in Brighton is invited, to discuss what matters to them, what kind of art they like, and what kind of work they would want BPT to create. The meeting has been scheduled after a full year of other BPT activity – including workshops in performing, writing or directing, play-reading groups, and post-show discussions – and feels like the first step towards a next stage: making an actual work together. That work could be anything, from a show for a big theatre like the Dome, to a performance that happens in Brighton’s streets. The point is for the people of Brighton to be involved at every stage, from the very first inkling of the idea to the fading light on the final performance.

When I arrive at the meeting (sheepishly late), the group are already deep in discussion, talking about the kind of drama – whether on TV or stage – they most enjoy watching and what it is they like about it. It’s not a question about style or content so much as emotional impact, and there’s a lovely, kind quality to the responses people give. Interest congregates around “stories not usually told”, featuring “heart-breaking, well-rounded characters”, especially those who are “morally compromised”, in work that is “honest”, and that offers a “humorous look at a difficult subject”. All of these feel like qualities to aim for.

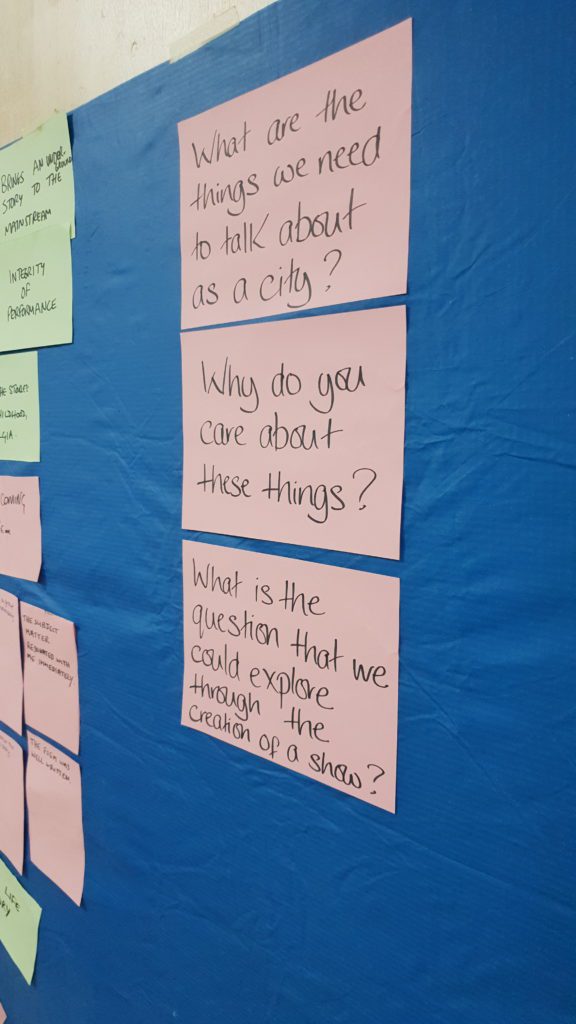

Having established the feeling they want to produce with BPT’s work, the group divide into threes and fours to think about what the collective work should be about. What story should it tell? Whose story should it tell? Not that Naomi and BPT executive producer Louise Blackwell ask these questions immediately or directly: instead they take a more circuitous approach, designed to get people thinking more widely but also more deeply. First they ask: what do we need to think about as a city? There might be an issue you’re discussing with friends, in private conversations, but would it benefit from being part of a more public conversation? Secondly there’s an invitation, for groups to make their own question, which could be explored through the creation of a show. Finally Naomi and Louise ask: why do you care about it? To me this is the most vital question of all: because without the passion of feeling deeply about an issue, why would anyone want to work on it – let alone anyone want to watch it?

As I move around the room, eavesdropping on the different groups, I quickly notice a shared set of concerns emerging. Poverty, homelessness and inequality are named again and again. There’s a fraught sense of injustice in the room, that there should be people living on the streets in a city that prides itself on its public reputation for being socially conscious or “right-on”, with its high population of LGBTQ+ people, Green voters, and vegan cafes. Quite a few people have direct experience of mental health provision in the city – or rather, lack of it – and raise that as a potential public conversation. And I particularly enjoy the animated debate about Brighton Pride and the ways in which it’s become an excluding, overwhelming, money-making machine.

But whether the groups are talking about Pride or homelessness, one question keeps nagging: what makes this issue specific to Brighton? That difficulty provokes another, with many in the room struggling to distil their discussion into a question that can be presented to the whole group. Naomi walks around offering encouragement, in particular reminders to think about her third prompt: why do you care? It’s worth repeating because it really feels integral to everything.

Once the questions are written on the orange paper and stuck to the blue sheet, it’s time – well, for cake, but after that – to gather into a single conversation again, to discuss form. Local theatre-maker Tim Crouch talked about form a lot in his Special Guest Workshop in September 2019, and it’s no doubt come up throughout the research year. How does the way in which work is made and performed not just enrich the story that is being told but enmesh with it, so that the telling and the tale are one and the same? The group sit in a circle around a large rectangle of paper on which Naomi has written the names of a variety of dramatic forms. Some are familiar: panto, soap opera, puppetry. Some need a bit of explanation: what, someone asks, is performance art? I duck my head while Louise talks about artists using their own experience and bodies to tell stories, and laugh at the end when she instructs me not to quote her on it.

Naomi’s next invitation is a fun one: to match the questions on the nylon sheet with a form. Who wants to see a comedy about the impact of gentrification? A dance about Brighton’s identity crisis? A puppet show about the climate emergency? As ideas criss-cross the group, Naomi marvels: “To me this feels like about 20 years’ worth of work.” But for the work to be meaningful, it’s got to have heart. And this wheels us back, not just to the question of why people care, but to a trickier section of the meeting I’ve so far skipped over.

Having shared their questions with the room, the group are invited to think about any stories of their own that might connect to the questions on the wall, just writing them down individually at first. Naomi takes care to stress that no one needs to share these stories out loud, unless they feel this is a safe enough environment for them to do so. It’s testament to the trust among the group that so many choose to voice them. This is where those questions that, for the most part, feel national in their scope and import become hyper-local, personal to Brighton’s inhabitants.

Many of the stories shared are heart-rending. One person talks about the death of his brother following a desperate experience within the mental health system. Another talks of the radical difference in educational opportunities experienced by herself and her siblings, a difference typical of the estate where they grew up. A third describes their embarrassment when needing to ask the council for food vouchers, another the fear of entering what are supposed to be supportive social care environments. Amid the gloom are chinks of radiant generosity: stories of homeless people who hand out Christmas cards to commuters and sweets to local children at Halloween. But with so much grief in the room, I’m not surprised at the end when one of the participants tells me that the meeting “felt like a therapy session” – not only in holding so much difficult experience, but in the way it’s left her feeling drained.

Undoubtedly these first-hand, intimate stories of life at the knife-edge of social inequality could make for powerful theatre – but at what cost to its participants? This is the question that has preoccupied Naomi in the weeks since the meeting. Her initial plan had been to take the material generated by the group to the weekly People’s Theatre Workshops, where it would be discussed further, honed, and slowly transformed into a fledgling performance. But, she says, “the subjects that came up were really depressing, and if we start working through these with people who are dropping in to the weekly workshops, it’s potentially going to feel unsafe”. Not only that, BPT has a “come and play” ethos: one that encourages joy in discovering your own creativity. “Focusing on the most challenging aspects of people’s lives,” she suggests, “doesn’t feel congruent with our values as a company.”

Her impulse is to find ways “that might feel safer for people to explore some of those issues creatively, without it feeling quite so personal and close to home”. When she made Tighten Our Belts in 2016 with an early incarnation of BPT – a group of participants who were all part of the Brighton Unemployed Centre Families Project – she did this by creating characters: instead of describing their own experiences of austerity, participants told lightly fictionalised stories, allowing more distance, anonymity and care. That might be a tactic she uses again – but for now, she’s trying a different experiment, using Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities as a lens through which to look at modern Brighton, an idea that emerged during one of the Special Guest Workshops. After six weeks of playing with that, she’ll review the situation again, and experiment with something else.

Whatever the outcome, three things clear: BPT’s commitment to openness, its resistance to hierarchy, and its desire to proceed with care for every participant, whether a regular who attends every session or a curious new person overcoming shyness to join in for the first time. These qualities are missing from so many public institutions and services, in ways that undoubtedly conditioned the questions and preoccupations raised by the group at the People’s Inspiration Meeting. It makes me think that there’s another simple slogan buried beneath BPT’s invitation to come and play, namely: “we care – do you?”